How to cook the perfect risotto

Risotto has a reputation for being high-maintenance. You can’t just ignore it while you go and do something else. It needs tending to, caring for. The process is undeniable. But if you follow the premise that what you put in is what you get out, if you give yourself over to the method, then you’ll forever reap the rewards.

It’s a simple dish, but a good one is always impressive. When I was training to be a chef in Italy it was the one dish I mastered straight away. To have Italians like your risotto, believe me, is a proper feather in your cap. I'll be showing you how to make a mushroom risotto with a mixture of dried and fresh mushrooms, but you can use the principles here to make any kind of risotto you like.

Watch Joseph create his perfect mushroom risotto (1:28 min)

The rice

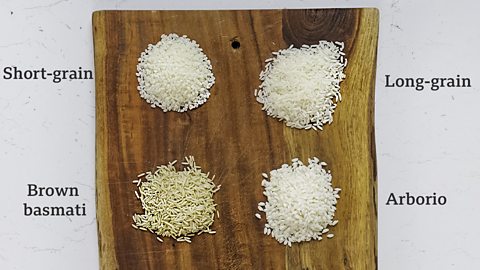

It sounds obvious but don’t make the mistake of cooking risotto with the wrong rice: choosing the right variety is essential. Arborio rice is the most widely available risotto rice and it’s a great choice. If you fancy an upgrade, carnaroli and vialone nano are the premium options for risotto, but they can be quite hard to get hold of in the UK.

Risotto rice has a short grain and is high in amylopectin starch. It's this starch, which is released by stirring, that produces the distinctive creamy texture. Long-grain rice varieties, like basmati, are lower in amylopectin, which gives them a fluffy and light texture. You can cook long-grain rice like a risotto, but it will never be the same.

At the opposite end of the scale, other short-grain rice varieties like glutinous rice (commonly used in East Asian cooking) are even higher in amylopectin starch than risotto rice, so much so that the grains stick together. If you tried to use glutinous rice to make risotto you’d end up with a sticky, coagulated mess – also not ideal.

Taking stock

The stock is the base of the risotto, the foundation of the dish. Because the rice absorbs so much liquid, using the best quality stock and wine you can manage will definitely improve the final result. Fresh stock will taste better than using a stock cube, and if you’ve got time you can make the stock yourself from vegetable scraps or a leftover roast chicken carcass. It’s quite a long process but it's great for tackling food waste and the results speak for themselves.

The tostatura and the sigh

Start by frying the base vegetables, usually onion or shallot, very gently. You don’t want them to brown at all, just become translucent and soft. You can fry with butter or oil, but butter burns at a lower temperature, so most recipes use oil and then add butter at the end of cooking to enrich the risotto.

Next add the rice to the pan and toast it for a minute or two. The fat will coat the grains and, as you stir, you’ll see them glimmer and shine. This step is called the "tostatura" in Italy, and it helps the individual grains keep their shape during cooking.

Once the rice is coated, add a glass of wine to the pan. The liquid will quickly sizzle and evaporate – a process called the "sigh" because of the sound it makes. This feels like an important moment when you’re making risotto, a sort of homage to the Italian-ness of it all.

After the rice has absorbed the wine, it’s time to start adding the stock.

Stirring it up

When it comes to adding the stock there are a couple of different schools of thought. For purists and Italians though, there is only one option: add a ladleful of hot stock at a time, and constantly stir until it is absorbed by the rice. The friction in the stirring agitates the grains, causing them to release their starch and create that rich texture. At the same time, as the liquid evaporates away, the flavours become concentrated and intense.

However, some people think that all this stirring is unnecessary. They say that all the starch is on the outside of the rice, so it doesn’t make a difference when you add the liquid. There are recipes which involve adding the stock all at once, and some cooks swear by baked risotto.

Still, doing it the traditional way is a safe bet for a delicious risotto: the rice grains all cook evenly and you don't walk away leaving it to burn or turn stodgy. But if you’re feeling experimental or if you’re in a rush, then give the no-stir method a try and see which you prefer.

The consistency I look for in a risotto is a soft, flowing mixture – like lava – with the individual grains of rice holding their shape and retaining a little bit of bite. The end of the cooking process is when you can stir in vegetables, seafood or mushrooms, which are usually cooked separately so they don’t overcook in the rice.

And then finally, beat in butter and Parmigiano-Reggiano to make the risotto extra rich and creamy – a final flourish called the "mantecatura". How much you add is up to you. Then, taste it and adjust the salt and pepper. And that’s it.

Serve with a final grating of Parmesan, and I think it calls for a fresh green salad on the side, too. Whatever the case, enjoy eating an Italian classic.